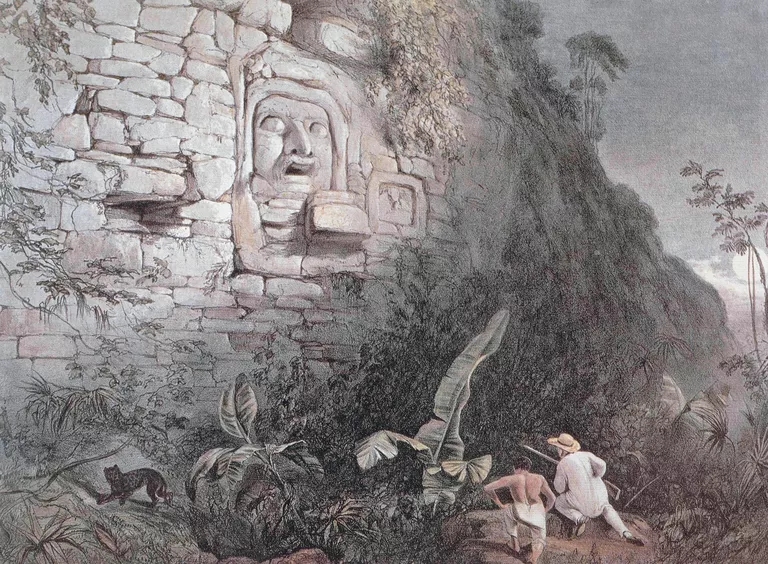

Maya or Mayan mythology is part of Mesoamerican mythology and comprises all of the Maya tales in which personified forces of nature, deities, and the heroes interacting with these play the main roles. The myths of the Pre-Hispanic era have to be reconstructed from iconography. Other parts of Mayan oral tradition (such as animal tales, folk tales, and many moralising stories) are not considered here.

List of Maya Gods and Supernatural Beings

Maya Religion, Mythology and Folklore

Mayan Origin Story: The Popul Vuh

This origin story was told by the Mayas, who lived in the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico from around 250 CE to 900 CE. It’s the beginning of a long, complex story called the Popol Vuh (literally the “council book”), first translated into alphabetic text from Mayan hieroglyphics in the 16th century. Now it still ripples, now it still murmurs, still sighs, and is empty under the sky. There is not yet one person, not one animal, bird, fish or tree. There is only the sky alone; the face of earth is not clear, only the sea alone is pooled under all the sky. Whatever might be is simply not there. There were makers in the sea, together called the Plumed Serpent. There were makers in the sky, together called the Heart of Sky. Together these makers planned the dawn of life. The story continues with the final people being made from corn, an important crop that enabled the Maya to move from being a hunting-and-gathering society to a more complex civilization.

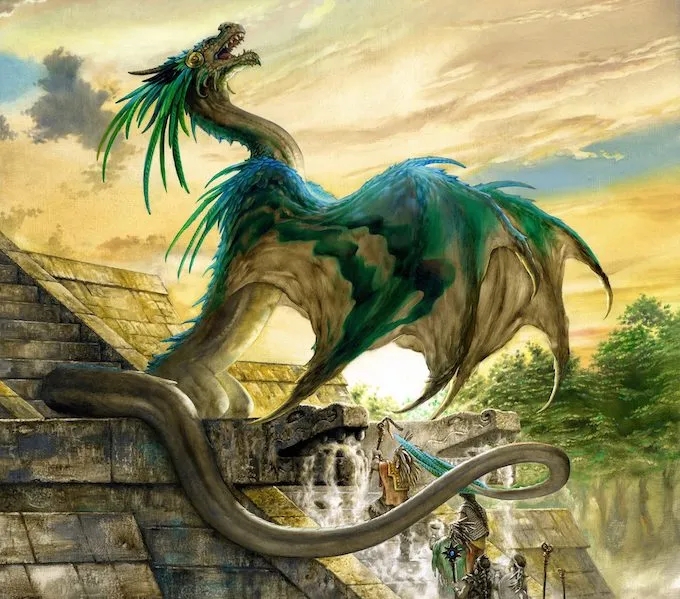

For the K’iche’ Mayans, animals were not lower beings but neighbours, alter egos and a way to communicate with the gods. Animals are everywhere in the Popol Vuh. They leap and lick and crawl and bite and squawk and hoot and screech and howl. They are considered sacred, not as disembodied beings in some faraway place, but in their coexistence with humans, day by day in the forests. The Sovereign and Quetzal Serpent, with its gorgeous blue-green plumage, birthed the world from a vast and placid ocean. The Popol Vuh provides the narrative of this creation of humankind and the subsequent mythology, history and culture of the K’iche’ Mayan Indigenous people in central highland Guatemala.

The ancient Mayans were advanced in many ways including art, architecture, mathematics, and astronomy. Mayan cosmology has been of particular interest in recent years. Some people believe that the Mayan calendar is predicting the end of the world in 2012, and this has brought a great deal of attention to the culture and civilization ancient people. The documents of the Ancient Maya are now under even more scrutiny as a result of this theory. Another important text of Mayan mythology is Chilam Balam, found in the Yucatan. Mythological passages in these books added to what was learned with the Popol Vuh.

Once the gods Tepeu the Maker and Gucumatz the Feathered Spirit made the Earth, they made beings to care for their creations and to praise them. They then created all creatures that roam the Earth today. However, these animals could not speak however much they tried. They could only bark, howl, bleat twitter, roar or moan. The disappointed gods decided to create better beings, ones who could do proper worship. The made the first race of men from wet clay and gave them life, but they crumbled apart soon after when they tried to speak. A second race of men was created, carved from wood.

The second race of men was stronger and able to walk, talk and multiply. However, these men did not have minds; their hearts were empty and they had no memories of their creation. Moreover, when they spoke it was empty and meaningless, so they could not praise the gods. Therefore, the Tepeu and Gucumatz sent a great flood to destroy them and ordered the animals to attack and tear them to pieces. Few of them managed to escape to the woods. They became monkeys and the gods left them there as an example to the next race of men.

The Aluxes (pronounced ah-lu-shes), were tiny beings made out of clay. Once they were created, they were given offerings and prayers to make them come to life. These creatures were hidden so that they could protect their owner that way. They are agile and light like the wind therefore they are scarcely spotted. Aluxes were faithful to their owners but mischievous to strangers. When properties of their owners are given to others, the aluxes would appear and scare the children. Therefore, to appease them, the new owners would gift them with food, honey, corn and cigarettes. Even today, the aluxes are believed to protect the Mayan towns and some believe that the aluxes bring light to the world. The Mayans also believed that if the aluxes were respected, they in turn would protect the people and their belongings.

The Mayans believed, like many people, that the heavens were above and the underworlds below and the human world was in-between. There are 13 layers piled above the Earth – the heavens. The Earth itself rested on a turtle or reptile floating in the ocean. Four brothers known as Bacabs held up the heavens. Below the Earth is the realm called Xibalba – the underworld with nine layers. The three realms are linked by a giant tree, whose branches reach to the heavens and the roots reach into the underworld. The gods and souls of the dead travel through the worlds along this giant tree.

Bacab [ɓaˈkaɓ]) is the generic Yucatec Maya name for the four prehispanic aged deities of the interior of the earth and its water deposits. The Bacabs have more recent counterparts in the lecherous, drunken old thunder deities of the Gulf Coast regions. The Bacabs are also referred to as Pauahtuns.

The Maya believed the Earth was flat with four corners. Each corner represented a cardinal direction. Each direction had a color: east-red; north-white; west-black; south-yellow. Green was the center. At each corner, there was a jaguar of a different color that supported the sky. The jaguars were called bacabs. Mayans believed the universe was divided into thirteen layers, each with its own god.

The Heroes Twins (or God Boys) are recurring characters from the mythologies of the indigenous peoples of the Americas. The specifics of each myth vary from tribe to tribe, but each story has a pair of twins (usually with magical powers) who were born when their pregnant mother was killed by the tale’s antagonist. Twins were considered unnatural in many cultures of this region, with beliefs about them having supernatural abilities.

Mayan Mythology

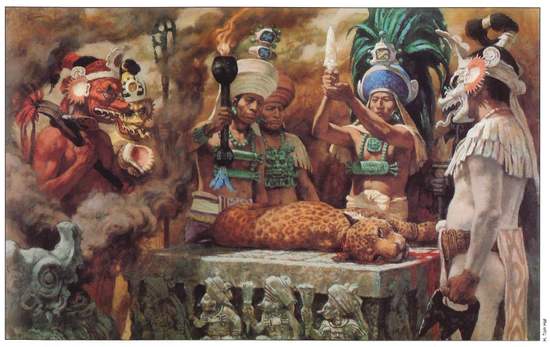

The Mayan had different myths. Mayan had many different gods and goddesses. The Mayan civilization made those sacrifices for the gods and goddesses. The Mayans always had festivals on different pyramids. Also Maya had made sacrifices for a very long time, for the gods and goddesses. Certain Mayan were asked to make sacrifices or animals, they were not commanded to make sacrifices. People or animals made sacrifices for the gods and goddesses. Some of the gods and goddesses are the God of Rain called Chac, a God of Corn, a God of Sun called Kinich Ahau, a God of the Moon called Ix Chal. Some more gods and goddesses are a God of War, a God of Sacrifice, Goddess of Birth, a God of the North Star, and God of all.

Kukulcán is known as the Feathered Serpent, one of the major deities of the ancient Mexican pantheon. Representations of a feathered snake occur as early as the Teotihuacán civilization (3rd to 8th century CE) on the central plateau. With Mesoamerican mythology spanning across so many regions, I’ve seen numerous ways of pronouncing the name including Quetzalcóatl, Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli and Kukulcán, if we are going with the Mayan interpretation.

Kukulcan, the Snake God of the Maya, Remains as a Legacy of the Once-Powerful Civilization

Kukulcan was the all-powerful snake god worshipped by the Maya. While little information remains about the legends and mythology of Kukulcan – due to the tragic destruction of the Maya codices by the Spanish conquistadors and Catholic priests – depictions of this god are in the surviving architecture of the Maya and remain as a lasting legacy of this once-powerful civilization. Whilst Kukulcan was a deity worshipped by the Mayas, his concept, i.e. a feathered serpent deity, was not unique to the Maya civilization.

He was known as Quetzalcoatl to the Aztecs and Gukumatz to the Ki’che’ (a Maya group located in modern day Guatemala). The idea of a feathered serpent god in Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican religion dates back to the time of the Olmecs, the earliest known major civilization in Mexico that flourished from around the 15 th to the 5 th century BC. The feathered serpent god is also known to have been worshipped by the people of Teotihuacan, as evident in the prominent depiction of this deity on the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, one of the major pyramids at the ancient site.

Itzamná: The Mayan Supreme Being and Father of the Universe

Itzamná (pronounced Eetz-am-NAH and sometimes spelled Itzam Na), is one of the most important of the Mayan pantheon of gods, the creator of the world and supreme father of the universe who ruled based on his esoteric knowledge, rather than his strength.

Itzamná’s Power

Itzamna was a fantastic mythological being that embodied the opposites of our world (earth-sky, life-death, male-female, light-dark). According to Maya mythology, Itzamná was part of the supreme power couple, husband to the elder version of the goddess Ix Chel (Goddess O), and together they were parents of all the other gods. In the Mayan language, Itzamná means caiman, lizard, or large fish. The “Itz” part of his name means a number of things, among them “dew” or “stuff of the clouds” in Quechua; “divination or witchcraft” in Colonial Yucatec; and “foretell or contemplate”, in the Nahuatl version of the word. As the supreme being he has several names, Kukulcan (underwater serpent or feathered snake) or Itzam Cab Ain, the “Itzam Earth Caiman”, but archaeologists refer to him prosaically as God D.

The Native Americans of North America and the Maya civilization of Central America are two cultures that existed long before any European set foot on the North American continent. And while the two cultures are considerably different, there is a thread of commonality between them and other cultures of the world that links them together throughout time. Both the Native Americans and the Mayans shared what almost every other culture across the globe shared in terms of mythological beliefs.

The Mayan and Native Americans spiritual belief system is characterized by animism (non-human entities are spiritual beings) or pantheism (a belief that everything is divine, not a divine being in everything which defines pantheism). This belief tied in everything from their daily lives, their surroundings and all of the natural world into one with their spiritual world as well.

Batman Existed in Mesoamerican Mythology and His Name Was Camazotz

Camazotz, (meaning ‘death bat’ in the Kʼiche’ Mayan language of Guatemala) originated deep in Mesoamerican mythology as a dangerous cave-dwelling bat creature. A cult following for the creature began amongst the Zapotec Indians of Oaxaca, Mexico and the figure was later adopted into the pantheon of the Maya Quiche tribe and the legends of the bat god were later recorded in Maya literature. In the Maya culture , the bat god Camazotz is linked to death.

Camazotz is also the name of a monstrous creature which inhabited a cave called “the house of bats” in the Popol Vuh . Most scholars believe that Camazotz was inspired by the common vampire bat, but others have suggested that it was based on a giant vampire bat that (probably) went extinct sometime during the Pleistocene or Holocene periods.

Chaac (also spelled Chac or, in Classic Mayan, Chaahk[t͡ʃaːhk]) is the name of the Maya rain deity. With his lightning axe, Chaac strikes the clouds and produces thunder and rain. Chaac corresponds to Tlaloc among the Aztecs. Like other Maya gods, Chaac is both one and manifold. Four Chaacs are based in the cardinal directions and wear the directional colors. In 16th-century Yucatán, the directional Chaac of the east was called Chac Xib Chaac ‘Red Man Chaac’, only the colors being varied for the three other ones. The rain deities had their human counterparts. In the traditional Mayan (and Mesoamerican) community, one of the most important functions was that of rainmaker, which presupposed an intimate acquaintance with (and thus, initiation by) the rain deities, and a knowledge of their places and movements. According to a Late-Postclassic Yucatec tradition, Chac Xib Chaac (the rain deity of the east) was the title of a king of Chichen Itza, and similar titles were bestowed upon Classic rulers as well (see below).