The Hakka (Chinese: 客家), sometimes also referred to as Hakka Han, or Hakka Chinese, or Hakkas, are a Han Chinesesubgroup whose ancestral homes are chiefly in the Hakka-speaking provincial areas of Guangdong, Fujian, Jiangxi, Guangxi, Sichuan, Hunan, Zhejiang, Hainan, and Guizhou in China, as well as in Taoyuan City, Hsinchu County, Miaoli County, Pingtung County, and Kaohsiung City in Taiwan. The Chinese characters for Hakka (客家) literally mean “guest families”. Unlike other Han Chinese subgroups, the Hakkas are not named after a geographical region, e.g. a province, county or city, in China. The word Hakka or “guest families” is Cantonese in origin and originally refers to the Northern Chinese migrants fleeing social unrest, upheaval and invasions in northern parts of China (such as Gansu and Henan) during the Qing dynasty who then sought sanctuary in the Cantonese provinces such as Guangdong and Guangxi, thus the original meaning of the word implies that they are guests living in the Cantonese provinces. Over the centuries, they have since more or less assimilated with the Cantonese people. Modern day Hakka are generally identified by both full Hakka and by different degrees of Hakka ancestry and usually speak Hakka Chinese.

The Hakka have been called guests, gypsies, nomads, barbarians, outsiders, even Mongolians. Among their progeny they claim the likes of Sun Yat Sen, Deng Xiaoping, Singapore’s Lee Kwan Yew and Taiwan’s Lee Teng Hui. But why, despite such well known figures, is their history and culture so poorly understood? Part of the reason, is that there is little consensus over where the Hakka came from. Early answers such as the possibility that the Hakka were descendants of Mongolian invaders have been summarily dismissed, given that many Hakka settlements predate Genghis Khan’s invasion. The most accepted theory today is that the Hakka are largely northern Han Chinese who progressively migrated south, fleeing war, poverty, and chaos. Whether these were deliberate migrations or chaotic retreats is a point of contention, but regardless of their nature, the hardships endured during these times have become a focal point in the Hakka creation story. The first migration took place at the end of the Eastern Jin dynasty, circa 400 AD, as a result of invading tribesmen. The collapse of the Jin caused a general exodus from much of the lands north of the Yangtze River. The ancestors of the Hakka left their homes on the plains of central China and made south for parts of Hunan and Jiangxi province.

Hakka, Chinese (Pinyin) Kejia or (Wade-Giles romanization) K’o-chia, ethnic group of China. Originally, the Hakka were North Chinese, but they migrated to South China (especially Guangdong, Fujian, Jiangxi, and Guangxi provinces) during the fall of the Nan (Southern) Song dynasty in the 1270s. Worldwide they are thought to number about 80 million today, although the number of Hakka speakers is considerably lower. They are considered to be a branch of the Han. Their origins remain obscure, but the people who became the Hakka are thought to have lived originally in Henan and Shanxi provinces in the Huang He (Yellow River) valley. They moved southward from there in two large migrations, one in the early 4th century and another in the late 9th century, perhaps to escape warfare or the domination of Inner Asian peoples. Their final migration in the 13th century took them farther south to their present areas of concentration. The name Hakka may have been derived from a Cantonese pronunciation of the Mandarin word kejia (“guest people”), which the northerners were called to distinguish them from the bendi, or natives. Alternately, it may have been a name the Hakka gave themselves when they migrated south. Having settled in South China in their own communities, the Hakka never became fully assimilated into the native population. Unlike most other Chinese before the 20th century, they shunned such practices as foot binding. Their language has affinities with both Cantonese, the language of the people of Guangdong province, and Mandarin, the language of much of northern and central China; many of the Hakka tongue’s initial sounds are a bridge between the two dialects.

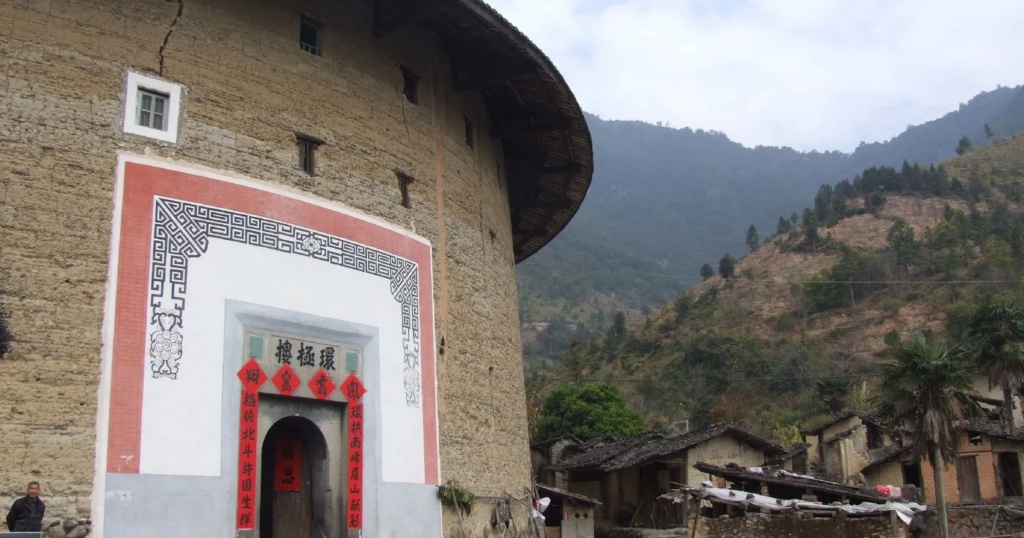

The Hakka people live in southern China, and the majority of the tulou villages are in the provinces of Guangdong, Fujian and Jiangxi. Of these, the tulou (meaning mud houses) in the rolling mountainous area of Fujian province are considered the most impressive and easily accessible either on tour or independently from Xiamen. A Hakka walled village (also called tulou, mud castles or roundhouses) are large communal clan houses made from rammed earth. Several families, often with the same surname, share a tulou and are still like one big happy family, even in this modern day and age. Each tulou can house between 150-800 people. A tulou is often three to four stories high, with a metre thick earthen wall forming the outside perimeter. Usually, only one entrance leads into the tulou – these Hakka walled villages were built as defence structures. They can be round, rectangular, square or oval in shape. Inside the tulou, each floor of the tulou serves a different purpose. The windowless ground floor was for keeping livestock, the second floor for storing grains, while the higher stories were (and still are) used as living space. The courtyard contains a well for water and communal space.

The Hakka, who are also referred to as Hakka Chinese or the Hakka Han, is a subgroup of the Han Chinese. They have a reputation as the ‘Jews of China’ because they were largely isolated and developed their foods, customs, and language, as well as going through multiple discrimination events and being forced to migrate to different regions repeatedly throughout their history. They are an interesting group of people, yet not much is known about them or their history. In this article, we look at some facts about them and why they have a separate identity from other Han groups in China, as well as their relations with other Chinese ethnicities. The Hakka Chinese are a subgroup of the Han Chinese whose Chinese characters translate to ‘guest families’, and their ancestral homelands are mainly in the provincial regions of the island of Taiwan, Guizhou, Guangdong, Hunan, Hainan, Zhejiang, Fujian, Sichuan, Guangxi, and Jiangxi. Hakka people’s migration from the north to the south of China happened during a time when earlier subgroups of Han Chinese already formed distinct languages and cultural identities from them. This is similar to what happened with the Chuanqing and Tunbao people, who are also Han Chinese subgroups that migrated to Southwest China from Eastern or Central China, and maintained unique ancestral customs that made them different from other Chinese people.

Origin and Migrations of the Hakkas

The Hakka people (Mandarin: Kèjiā rén 客家人, literally “people from the guest families”) are an important minority “ethnicity” in southern China, speaking a distinctive language, and living in distinctive but discontinuous communities in Guǎngdōng 广东 Province and, to a lesser extent, Fújiàn 福建 and Táiwān 台湾 Provinces and occasionally elsewhere. Linked to the term kè 客, or “guest,” Hakka have traditions of having migrated from somewhere else, probably somewhere to the north. (The Hakka language is sometimes described as “somewhere between” northern Mandarin and southern Cantonese.) Not surprisingly, this has given birth to silly ideas about the Hakka being the only “pure” Chinese or the Hakka being “half-breed mixes of Chinese and savage southern tribes,” and such notions have long been discredited. But for the historian the term “guest,” the language difference, and the traditions of migration in the remote past combine to suggest that the original differentiation of this people and the history of its probable peregrinations can be a matter of some interest. Unfortunately, whether one views the data as rich or as scant, it has proven difficult to achieve perfect clarity about Hakka origins.

The Hakka are usually found in the less habitable regions of China and South-East Asia, as with most tribes who have emigrated away from their homelands. Today there are tens of millions of Hakka in the Southern Chinese provinces of Guangdong, Jiangxi, and Fujian. In the last century the have also migrated to Europe, the Americas, and Africa. The majority of the population of China is derived from the Han people. The Hakka are a unique ethnic sub-group of the Han. Their ancestral history is neither straightforward or clear, but it is thought that they were originally from northern China, but they were forced to leave during the fall of the Southern Song dynasty in the 1270s. The name Hakka is a Cantonese pronunciation of the Mandarin word Ko Chia (“guest people”), Around seven percent of Chinese align their roots to the Hakka. Despite their numbers, the Hakka never became fully assimilated into the native southern population. They have well-preserved traditional beliefs and cultures and are thought to be of royal blood. If so, their practices are reflective of the cultural practices of the Chinese nation 20 centuries ago, although the culture has not been kept pure as they have inter-married with other ethnic groups and absorbed their cultures. They are a very resilient and hardy group of people, for example, the most northerly restaurant in the world is supposedly a Chinese restaurant run by a Hakka.

The Hakka believe themselves northerners, direct descendants of nobility from the Yellow River cradle of Chinese civilization. When moving south they were shut off from prime land in flat areas and forced to move uphill (some content they “naturally” did so, having also lived in northern upland regions), developing skills and sociocultural traits “natural” to the working of poor high-hill soil and excelling in mining and forestry. Their dialects are southern and young in origin (two are spoken in Taiwan), showing traces of other Chinese dialects. The term “Hakka” or “guest people” is of Cantonese origin. They number about four million, about 15% of Taiwan’s population. Their path through history is shrouded in mist and mystery, but a general map can be drawn. It is thought they came south in stages from China’s northern regions, in the great southward Han Chinese migration. Moving into the hilly areas south of the Yangzi River, en masse yet in stages, their other Han Chinese brethren did not then see them as being of the same race, though in fact the Hakka share most physical/ cultural traits. Working on tea plantations, it was common for the Hakka to sing as “talk” to each other. Often this took the form of back-and-forth flirtation between young men and women. From the traditional field songs simple and lighthearted skits took shape, ultimately meshing in the distinctive Hakka opera, often called “three-legged tea picking opera” because no more than three performers take the stage and, in Taiwan, the same tea-theme story is always told, in different versions. No falsetto here — natural voice only. (Incidentally, it is mostly Hakka women who handle the hard work of picking Miaoli’s famous version of Oolung, Oriental Beauty Tea.)

As the largest of the four indigenous tribes in Hong Kong, the Hakka tribe has been a potent driving force in shaping the history, values, and cultural landscape of our city. While traces of their legacy may be hard to detect when we are ensnared in the tangle of neon signs and skyscrapers, venture further afield beyond the urban gridlock and you will find that tangible vestiges of traditional Hakka heritage are still present across the countryside of the New Territories. Preserved in the form of semi-deserted rural settlements girdled in greenery, these living relics may be easy to overlook, but housed within them are fascinating stories that bridge the gap between Hong Kong’s lived culture and colourful past. Join us as we chart the history of the Hakka tribe in Hong Kong and find out how you can encounter Hakka culture up-and-close with newly launched experience platform Mylocals! If the name “Hakka” (客家)—which literally means “guest people” in Chinese—is any indication, the tribe has historically been built on migration. Originating from the northern plains of China, the Han dialect subgroup began emigrating to the south from as early as the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC) to escape social upheaval and nomadic invasions, and continued their southward exodus over the course of many dynasties. In the earlier waves of their dispersion, they made their bases in southern provinces like Guangdong, Fujian, Jiangxi, and Sichuan.

Hakka people used to be the target of discrimination and hatred from other ethnic Chinese. In the Qing Dynasty, there was an anti-Hakka genocide that killed 30,000 Hakka people per day. Then, there was the Punti-Hakka Clan War which killed up to 500,000 Hakka. This conflict between Cantonese and Hakka lasted from 1855 to 1867. A similar conflict at almost the same time also occurred between Cantonese and Hakka in Perak, Malaysia. Hakka are scattered in Aceh, Belitung, Bangka, and West Kalimantan. The Hakka people in Jakarta usually live in parts of West Jakarta. As another sub-group, the Hakka people living in Jembatan Lima, Glodok, Krendang, and Jembatan Besi are known as “Chinatown”, and usually work as shops and restaurants owners. Hakka cuisine usually tastes salty and is very oily or fatty, and is dominated by savoury stir-fries. Understanding how Hakka people used to get persecuted so much, their cuisines are mostly fermented, meaning they were able to preserve food during a crisis. To try Hakka specialties, you can come to the Krendang area in West Jakarta. Popular dishes to try include mixed rice, kincipan, and srikaya bread.

Hakka people, who are found throughout the Chinese mainland and southeast Asia, began settling in Taiwan in the early 18th century. This Han Chinese ethnic group has its own language and customs, preserved despite numerous scatterings and migrations over the past 1,600 years. Particular deities in the Chinese folk pantheon are regarded as Hakka gods. And unlike Hoklo families, Hakka parents never bound the feet of their daughters. Taiwan’s three million Hakka people are concentrated in the northwest and in a few towns in the far south, because by the time they arrived on the island, the best farming land had already been taken by Hoklo settlers. Consequently, the Hakkas had to make do with marginal and foothill areas. Hakka people are respected for educational success and hard work. Meinong, a exceptionally picturesque town in Kaohsiung, is said to have produced more PhD holders relative to its population than anywhere else in Taiwan. Lee Teng-hui (b1923), a Hakka who has a PhD from Cornell University, became Taiwan’s first native-born president in 1988.

Strewn across the hills where the three provinces of Fujian, Jiangxi and Guangdong merge, the colossal Hakka earth buildings (Kejia tulou) are a mesmerising picture of an ancient but slowly disappearing way of life. For anyone numbed by the impersonal nature of modern Chinese apartment blocks or the frenzied pace of urban China, the earth buildings are enchanting reminders of communal village life and the ancient rhythms of the agrarian southeast. In times of need, the Chinese frequently intone, “A nearby neighbour is better than a distant relative.” The earth-building-living Hakka have the best of both worlds, as neighbours are also relatives, as is the case in many traditional villages across China. The Hakka (in Mandarin: Kejia, meaning “guest people”) – who live in scattered pockets across south China and speak their own dialect – originally migrated from a central region of China around 1,500 years ago. The name “guest people” suggests a tribe on the move, which was once the case, as the Hakka were continually displaced by war, persecution or famine.